Introduction

We are looking at a high-level overview of analytical mindwork. Later this week, I’ll break down many of these concepts more fully.

Mindwork is complicated because it involves some analytical, creative, and contemplative skills. Of the three types of mindwork, analytical mindwork and analytical skills are the most measurable, which is why they are typically included in job descriptions.

Even if the actual thought processes themselves are not easy to observe, the outcomes are more tangible than some other forms of mindwork. One of the reasons for this is:

The methods employed by the analytical worker are not necessarily the product of an analytical mindset.

There are a number of valuable and models that exist (e.g., Lean Methodologies, the Five Why's, etc.), but the use of, or adherence to those models does not demonstrate that an employee is an analytical thinker.

The word analytical has come to mean someone who utilizes analytical methods or has the capability to break down something into its core elements. Analytics comes from the same root word, and is concerned with identifying good arguments.

When you think of someone who has analytical skills, you might not think of someone who is persuasive. But ultimately, analytical methodology is the application of tools that verify perspective or direction as being better or worse than another. While it might not be used to persuade anyone, analytical work is inherently persuasive (meaning that it induces though or actions through an appeal to reason).

All analytical models are, at their core, logical steps or conditions used to distinguish between valid and invalid arguments.

The capability to apply a particular analytic model precisely in the right situation is not necessarily an outcome of skill. Rather, it is the outcome of traits; in particular, conscientiousness. Conscientious could be defined as being dependable and organized, so we could describe analytical mindwork as both a natural approach demonstrated in a set of skills. However, as we will see later on, the environment that influences the development of a person’s traits, including analytical thought, can alter the accuracy of that natural analytical ability.

For this reason, while analytical skills might be measured by organizations, especially during the hiring process, what is actually being measured is conscientiousness. They are ‘measuring’ the conscientiousness trait with a binary standard, usuaslly drawn directly from the educational concensus associated with the industry or field.

For example, an individual who is educated in mechanical engineering, and who is considered analytical is someone who is simply a conscientious applicator of the standards of mechanical engineering. While this can be observed and measured to some degree, the ‘skills’ are actually traits. It is very likely that these traits existed well because the individual started their career.

Granted, there are certainly roles which must follow standardized analytic application, but the obvious question is why that application is seen as a ‘hard skill’ when it is, at its core, the outcome of a well-developed trait.

Perhaps these traits are referred to as hard skills in order to maintain purity within the industry; effectively eliminating unapproved analytic models from breaking into the space by simply classifying certain personality traits as certifiable skills. Organizations that are concerned with reliability will always prioritize personalities which naturally reflect reliability.

The issue here isn’t the assessment of personality traits. It’s the misunderstanding of what traits and skills actually are.

Skills are things which can be taught, and most importantly, things someone can have without being personally invested. A disinterested and disengaged employee who has the skills, but doesn’t care about the underlying outcome, is a minefield for any organization. These types of employees are prone to corruption, bribery, and theft. This puts your organization and your clients at risk.

Organizations prioritizing the unchanging application of a specific analytic, at the expense of trait development, risk employing two types of operators:

Cognitively stagnant operators who are less capable in situations requiring innovation or outside-the-box thinking.

Personally unmotivated operators who are apathetic about the organization’s success and impact for clients.

Engaged employees are obviously happier, but they are also less of a risk for the organization. The key to finding these associates is in the use of trait-based assessments. These assessments determine the nature and objective of the role, rather than simple skill tests. For example:

Anyone who understands the Dewey Decimal System could work as a librarian, but only someone who is passionate about books, reading, and learning will be able to cultivate an environment that increases the use of the library.

In the same way, analytical skills, or the ability to properly apply an analytical model (in our example, a library cataloging system) are not necessarily supportive (and sometime counterproductive to) the ultimate goal of an organization (in our example, increasing love of reading and use of library books). It turns out, personal interest and passion about the subject, coupled with natural traits (probably conscientiousness) will have a great chance of long-term success.

So what does this all mean?

The natural interest and trait-driven behaviour of your associates has more to do with their capability and skill than any other single factor.

We have all worked with someone who was trained just as well as us, and was just as skilled in a task as we were, but who, for whatever reason, did not care about the job or the outcomes for the clients. Even if they followed every step precisely, the impact and outcome was often clearly different for the clients. Working with these people is always more difficult, and managing is usually frustrating.

Let’s talk about the role of passion.

The root of our English word, passion, comes from the idea of suffering or enduring something difficult. In our world, we use passion to refer to someone’s enthusiasm about something. It’s not a great leap; those things we are passionate about are appealing enough to give us motivation to endure great difficult to attain them.

The two sides of passion can be seen in a personal romantic relationship. On one hand, the lover desires and admires their beloved. It is precisely that deep enthusiasm and affection which allows them to bear incredible burdens, or go through intense suffering, all int he name of pursuing (or retaining) the relationship.

In the same way, employees within an organization have personal passions, and are therefore willing to suffer deeply, in order to pursue those passions. As it has been crudely observed, ‘every job has a crap sandwich.’ What this means is that no mater what you do, even if you love it, there are elements of the job that are just awful.

A classic example of this idea is the challenge of a writer. The writer loves to write, and at times can write without any effort. However, the ‘crap sandwich’ in this case is the deadline. And the editors.

Deadlines rush and hurry the writer, forcing them to move faster than they might otherwise prefer. This of someone rushing you to finish your gourmet meal; the meal is great, the atmosphere is decidedly not.

Editors, on the other hadn, humble and demoralize writers; calling into question their grand ideas and slamming the door of reality (or grammar) in their face. Think of someone who takes the time to make it painfully clear to a child the statistical chance that they will, in fact, grow up to be an astronaut.

We think of editors as literary highwaymen, brutalizing the poor writers they happen upon, when in actually, editors help the writer sculpt his masterpiece. By pointing out additional places the chisel must still cut, and the hammer must again fall. The book is the masterpiece of the writer, but the writer is the masterpiece of the editor.

Passion and Performance

Identifying the natural passions and personality traits of your employees will help you to synchronize their personal goals with their workplace goals. This naturally increases their resilience. Since they will be willing to put up with so much more crap than they would have if they were not personally invested.

There are limits to this type of organizational approach, however. It is important that business leaders do not follow the psychological and military leaders from the first world war, who thought they could manipulate psychological interest in recruits to make them into super soldiers who were impervious to the psychological ravages of warfare.

From a Utilitarian perspective, super soldiers make some sense. They would be good at killing, and doing so without breaking down. However, it turns out that the healthy human mind is not designed to take life without severe psychological repercussions. A ruthlessly efficient soldier would be able to kill without thought or feeling, but that soldier is a major danger and risk to society outside of the battlefield.

One of the silver linings to the existence of PTSD among veterans is that their psychological trauma indicates a normal human mind, which recoils at death and descruction.

Organizations which hope to take advantage of their employees by synchronizing their traits and goals, without also attempting to solve for the crappy parts of the job, will burn out their highest performing, and most passionate associates.1

The goal of the trait development is to unlock individual potential by eliminating natural barriers and boundaries between personal passions and business outcomes. When an organization manipulates this system without sincerely attempting to eliminate the challenges of that job, they slowly sap the enthusiasm reservoir of their employees.

In other words, the organization that ignores the small problems that irritate their employees cultivates a culture of hopelessness.

One of the fastest ways to build trust with your team is not through MAJOR changes, but to quickly resolve the small issues that have been irritating them for a long time. Think of a pebble in your shoe. Rapid changes to those small points of pain function as a conduit to deeper trust and vulnerability between employees and their manager. There is a reason so many people see the truth in the words of Jesus, “Whoever can be trusted with very little can also be trusted with much.”2

When an organization proves themselves at solving small concerns, they build a foundation of trust to to bear even bigger issues from their associates. This trust is absolutely critical, and often eliminate organizational crises before they really even get started.

In this book, Creating the Accountable Organization, Mark Samuel describes what he calls “proactive recovery.”3 Proactive recovery basically allows organiations to avoid a crisis and limit the impact of the original mistake on overall performance. Of course, this cannot happen in an organization where trust is not cultivated.

More Mindwork

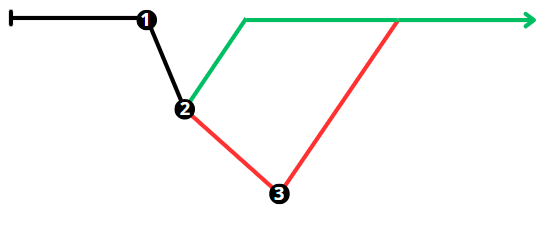

The analytical mindworker is continually applying systems, processes, tools, and formulas, in short, an analytic, to everything they do. This does not mean that they cannot be creative or dynamic. Sometimes they may have incredible ideas, innovations, or approach things in a random, unpredictable way. But the through line for an analytical mindworker is the tendency and capability to effectively divide up their work into smaller, more manageable pieces.

Later this week, we will discuss some models and tools used by analytical workers, as well as the basics of analytical cognition, and the traits that influence it. The method of measuring analytical mindwork is, as we have discussed before, much easier than mindwork in general.

Conclusion

Mindwork is complicated, but the analytical mind, and the associate who is capable at applying an analytic to problems, is an invaluable resource. Importantly, we have to remember that what makes someone an analytical worker is not whether they can do analytical work.

What makes an analytical mindworker is the way they naturally apply an analytic to a situation.

Many people think of analytical mindworkers as cold, pragmatic, logical, and heartless. But this is prejudicial. All of us, in almost every area of our life, apply an analytic standard—we just don’t think of it that way.

You compose an email: How do you greet the other person? What do you dsicuss first?How much do punctuation and spelling matter, or does that depend on who it’s being sent to? How long should it be? Should you discuss multiple topics, or just keep it to one?

Any question you may have about how to do something is an analytic question. Further, whatever answer we give is also usually filtered through an analytical framework. We live our lives carrying around innumerable pairs of glasses which we use to understand our world. If something is strange or unfamiliar to us, we start asking other people to borrow their glasses to see if we can make sense of what we are seeing.

Analytical people are not unfeeling or cold (although anyone can be), instead, they are naturally better at finding a pair of glasses that makes sense of their circumstances or situations. They might not seem to have the same emotional reaction as everyone else, but that is because their emotional reaction is, to some degree, subsequent to the ontological question of their experience. That is to say:

The analytical person often doesn’t know what to feel until he understands what has happened, or is happening.

If he understands the context and the analytic for a scenario, situation, problem, or interpersonal conflict, he can determine which emotion makes the most sense to reach a desirable outcome. Of course, there can be a delay here. So overly analytical people can seem cold at first, then socially awkward while they are sifting through their emotions to determine which makes the most sense to them.

Analytical mindworkers provide an essential service, even if they are sometimes difficult to understand. Later this week, we’ll discuss more about what influences their approach, and how they can make your organization more successful.

I am working on a future post of micromanaging, and the implications for leaders. This is more than an unethical business practice, it is actually an anti-human practice. Besides, it undermines the leader’s authority itself.

Luke 16:10a, New International Version.

Mark Samuel. (2015). Creating the Accountable Organization. Xephor Press. pp. 115-121